AARP – The Extraordinary World of Music and the Mind

It can remind you of the best days of your life. It can comfort you. It can even make those who remember little sing again.

By John Colapinto, Published November 22, 2023

Part I “Hey Jude”

In 2007, a young man named Colin Huggins began playing music on the streets of New York using a battered upright piano he’d bought on Craigslist.

He was a former accompanist for the American Ballet Theatre, but playing and singing pop songs outdoors had convinced him of the almost mystical power of music to soothe, delight and heal his fellow New Yorkers. He began to push the piano all over downtown, even managing to get it onto a subway platform at 14th Street.

There, in December 2008, he was caught on a blurry cellphone video, later posted to YouTube, playing the Beatles’ “Hey Jude.” In the course of two minutes, the potentially dangerous netherworld of the New York City subway — the very definition of existential alienation, where eye contact is assiduously avoided — was transformed into a place of joy, camaraderie, connection.

At first, four or five college-aged kids began to sing along (“take a sad song and make it better”), and by the time Huggins hit the crescendo (“better, better, BETTER”), a group of middle-aged businessmen in long black coats on the opposite platform were singing too. With the irresistible coda (“nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah-nah-nah-naaaah”), everyone on both platforms — male and female, Black and white, young and old — was singing, clapping, smiling at one another. The transformation was miraculous.

That video is testament to how melodies and lyrics lurk in our brains, ready to be released at the sound of a few notes — lifting our spirits, connecting us with our fellow human beings and evoking deeply buried memories as powerful as anything in the human experience.

For more than 50 years, the medical specialty known as music therapy has harnessed this extraordinary aspect of music to treat diseases ranging from depression to chronic pain to movement disorders to autism to Alzheimer’s disease. But only in recent years has the scientific community begun to penetrate the mystery of how something as ephemeral as an acoustic signal — mere air vibrations — can have such profound effects on damaged bodies and brains. In the process, experts are gaining a deeper understanding of the importance of music in everyone’s day-to-day life, and its astonishing effects on the healthy, normal brain.

That music has been a part of human cultures since time immemorial is attested to by early man-made fossils — including various percussion instruments and a 60,000-year-old flute made from the femur of a now-extinct European bear — to say nothing of the original musical instrument, the human voice, whose remarkable music-making properties have given it a central place in virtually all forms of religious worship, from the chants of shamans in Indigenous tribes, to Islam’s haunting call to prayer, to the extraordinary overtone singing perfected by Buddhist monks in Tibet, to the hymns and psalms of Judaism and Christianity. According to historian of religion Karen Armstrong, “Scripture was usually sung, chanted or declaimed in a way that separated it from mundane speech, so that words — a product of the brain’s left hemisphere — were fused with the more indefinable emotions of the right.”

Recent scientific studies have shown that music’s power over us is not purely psychological but based in measurable physiological changes. Singing along with others to a beloved song (such as “Hey Jude”) causes the brain to secrete the chemical oxytocin, a naturally occurring hormone that creates the warm sensations of bonding, unity and security that make us feel all cuddly toward our children and others we love; infuses us with feelings of spiritual awe; and can alleviate chronic pain or the debilitating sensations of anxiety or the isolation of autism. One area of medicine where the power of music has been particularly remarkable is in the treatment of the dementias, including Alzheimer’s disease, whose stubborn and terrible symptoms have been resistant to most forms of treatment.

Part II “Fly Me to the Moon”

On a recent afternoon, I visited the 80th Street Residence, an assisted living community for dementia patients on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Seventeen patients gathered in a community room, and staff members helped seat them in chairs that faced the front of the room, where Xiyu Zhang, a 37-year-old music therapist, introduced herself to the group. Her audience stared back, blankly. (“They don’t all remember me,” she later told me. “They see me every two weeks, but many don’t know why I’m here.”)

She began strumming an acoustic guitar and singing: “Fly me to the moon / Let me play among the stars / Let me see what spring is like …” The effect was immediate. Chins lifted from chests, eyes opened. Smiles flickered on one or two faces. A woman began to sing certain phrases: “on Jupiter and Mars … in other words … hold my hand.”

Over the next 45 minutes, Zhang fanned the fragile spark of group attention into a steady blaze with a string of standards (“Blue Moon,” “Catch a Falling Star,” “You Are My Sunshine”) and got nearly every person singing along. Between verses, she called out questions: “Who sang ‘Singin’ in the Rain’?” A white-haired woman said, “Gene Kelly!” “What is the girl’s name in Wizard of Oz?” A woman in the second row blurted out, “Dorothy!” “And her dog?” “Toto!” “That’s amazing!” Zhang cried.

And it was amazing for people who, before the music started, would not have been able to recall the names of family members or the career they had pursued for 40 years — or been able to break free of the inward-turning silence in which the disease had wrapped them.

Indeed, isolation is one of the most frightening and unsettling symptoms of the memory loss that’s synonymous with Alzheimer’s and other dementias — a memory loss that separates a person from their very self. For what are we, ultimately, but the sum of our personal recollections? At the end of Zhang’s session, as the patients were led back to the elevators, the mood was a little like a bubbly cocktail party breaking up. Restored for the time being to a sense of self through the activation of better-preserved neural networks, the patients traded words and laughter with caregivers and one another — a transformation as miraculous as that of those commuters on the New York City subway platform. Indeed, more so.

Music therapy’s roots date back to World Wars I and II, when service members with traumatic brain injuries and “combat fatigue” (now called post-traumatic stress disorder) were discovered, by chance, to improve in mood and function when listening to music. Veterans hospitals began hiring musicians to play to patients, and it was not long before physicians realized that the treatment’s effectiveness would be enhanced if musicians learned the basic tenets of psychology, neurology and physiology, so that they could tailor their playing to a patient’s specific needs. Michigan State University launched the first degree program in music therapy in 1944.

Music and Memory

Part III “Let Me Call You Sweetheart”

Concetta Tomaino was 24 years old in 1979 when she graduated with a master’s degree in music therapy from New York University. She would go on to become a pioneer in the use of music to treat dementia, and today, at 69, she is a legend in the field, the dedicatee of neurologist Oliver Sacks’ 2007 book Musicophilia, the past president of the American Association for Music Therapy, and the executive director and cofounder of the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function housed at Wartburg, a senior living facility in Mount Vernon, New York, where I recently visited her. Cheerful and soft-spoken, with a round face and curly brown hair, the Bronx-born Tomaino was, she says, “a big science kid.” But she also played accordion and trumpet. In college, she blended her loves of music and science when she decided to switch from premed to a degree in music therapy.

Tomaino was still a student intern in 1978, fulfilling the 1,200 hours of clinical fieldwork necessary for her master’s, when, at a nursing facility in Brooklyn, she encountered her first dementia patients — a population not then generally considered to be candidates for music therapy.

As was common in that era, the dementia patients were severely neglected: heavily drugged, hands encased in mittens to prevent their clawing at themselves, outfitted with nasal gastric tubes for feeding, and left to scream and wail in confusion and anxiety on an upper floor of the facility. “Nobody went up there,” Tomaino recalls. “It was this horrible, horrible place. The cacophony!” A nurse told her, “Oh, it’s so sweet of you to come, but they don’t have any brains left, so don’t expect too much.”

Tomaino refused to believe it. She lifted her accordion and started playing the opening chords of “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” a hit tune published in 1910 that became even more popular when Bing Crosby recorded it twice, during the Depression and World War II.

She began to sing: “Let me call you sweetheart / I’m in love with you …”

“The noise stopped,” she remembers. “People opened their eyes. Half of them started singing along: ‘Let me hear you whisper / That you love me too.’ ”

The nurse looked at Tomaino in shock. “She said, ‘What just happened?’ ”

Two years later, Tomaino was hired as the music therapist at Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx — where Oliver Sacks was a neurologist. He was already famous for his 1973 book Awakenings, which chronicled his use of the experimental drug L-dopa to awaken patients who had been “frozen” for decades in a coma-like state from a virus called encephalitis lethargica. Tomaino saw an obvious parallel with dementia patients. “So I said to Oliver, ‘Did you ever see this?’ He said, ‘No! Show me!’ ” Sacks was floored. “He said, ‘We gotta look at this and figure out what the heck is going on!’ ”

Through the 1980s, with Sacks’ input, Tomaino studied the positive effects of music on the mood and memory of Beth Abraham’s dementia patients. The work drew increasing attention after the 1990 release of the movie adaptation of Awakenings, and reporters descended on Beth Abraham in search of new medical miracles. In a joint interview with The New York Times in 1991, Sacks called music a “neurologic necessity,” and Tomaino said that music could “locate the lost personalities” of dementia patients — a phenomenon she demonstrated that same year on a segment of the TV show 48 Hours when she played a swing tune on her accordion for a near-catatonic dementia patient, who jumped out of his wheelchair and started dancing (he had been in a dance act with his brother in his youth). “The staff got really excited,” Tomaino says, “so the physician assistant would sing to him, the orderly would sing to him as they walked. He eventually went back home to his daughter.”

Two years after that, Tomaino convened the first-ever conference on Clinical Applications of Music in Neurological Rehabilitation. “The scientific and medical community was still on the fence about music and the brain,” she recalls. “We hoped to push the dialogue. We had over 125 people show up, some from outside the country, and we needed to send some away.” This gave Tomaino the momentum (and the funding) to help launch, in 1995, the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function at Beth Abraham. Since then, there has been an explosion of interest in the field of music and memory.

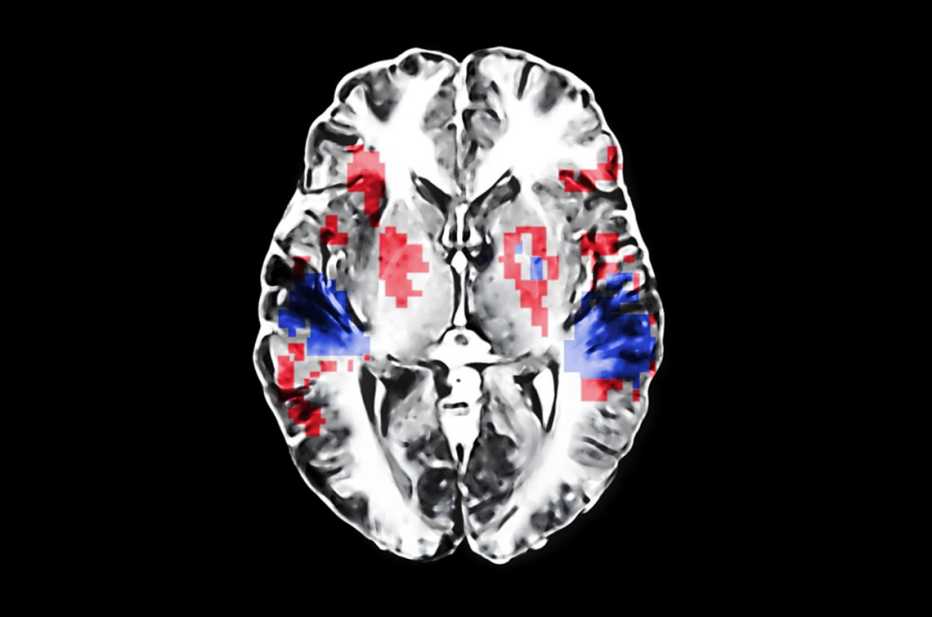

Mysteries remain about how memories are created, stored and retrieved in the brain and how music acts to revivify them in dementia patients, but answers have begun to emerge, thanks to advanced brain scanning technology that did not exist when Tomaino and Sacks did their early research — specifically, fMRI. This technology uses a strong magnetic field and radio waves to track blood flow throughout the brain, showing what areas are active during physical tasks, like moving the fingers (which “lights up” areas of the motor cortex in an fMRI scan), or during cognitive tasks, including decision-making and memory.

All memories, regardless of how vivid and indelible they seem to us, are electric and chemical signals in our brains that travel through a network of neurons. Decades ago, it was believed that there was a dedicated memory module of the brain where the past was stored. fMRI revealed that many areas of the brain are involved with memory, from the brain stem (seat of automatic tasks like breathing and blinking) and the emotion centers (including the amygdala, with its fight-or-flight reflexes) to the seeing and hearing centers; from the executive areas of the brain (where thinking and decision-making occur) to the part where long-term memories are processed.

None of this should be especially surprising when you consider the layered richness of memory — the distant sights, sounds, smells, feelings and conversations that can be evoked by something as ephemeral as a scent on the breeze.

Memories begin with our five senses, through our experience of the world. The memory that allows you to recognize your mother was first encoded when you were a baby, from seeing, hearing and smelling her — sensory stimuli that resulted in the firing of neurons that wrote the memory “Mom.”

Through repeated exposure to your mother, that memory grew increasingly durable, owing to actual physical changes in your brain. When specific groups of neurons are repeatedly activated, they strengthen the synaptic connections between them. (“Neurons that fire together wire together” is the saying in neuroscience.) Which is how a memory vital to your continued existence — That’s my mom! — becomes strongly encoded and efficiently accessed.

But even the memory of your mother can be lost if something chokes off the electrochemical signals that flash along those neurons. This is what is thought to occur with Alzheimer’s disease. Certain brain waste products — so-called tau tangles and amyloid plaques — as well as other factors, the theory goes, can disrupt and destroy neurons and their connections, especially in areas of the brain associated with memory — even as strong a memory as Mom.

Alzheimer’s is progressive. As more brain cells die, more of the past vanishes. Of all the attempts to hold on to memories in the face of this loss — through drugs, diet and exercise — music has proved to be among the most successful. Again, fMRI offers a possible explanation for why.

Listening to music, fMRI reveals, is (like memory itself) a full-brain workout; a wide distribution of brain structures light up, including the:

- Brain stem. Rousing classical music makes the pulse and blood pressure rise; soothing lullabies make them drop.

- Motor centers. These are the source of the irrepressible urge to tap the toe or bob the head in time with music.

- Language centers. They light up to a song with lyrics we remember.

- Auditory cortex. This is where music’s pitches and tones are processed.

- Emotion centers. Here feelings of yearning, joy, exultation, sadness, fear or loss are touched off by changes in the music’s tempo, pitch, volume; in the executive centers, thoughts and memories connected to the music are activated.

- Visual systems. Think of how a dark and stormy passage of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony can call up images in your mind of black and turbulent skies. Disney did it for us with “Night on Bald Mountain” in Fantasia.

This full-brain workout hints at why melodies and lyrics — particularly those from songs that have personal significance to us — have such a peculiar sticking power in our memories. fMRI scans reveal that such “auto-biographically salient” music is written into many parts of the brain — the movement center, for instance—not touched by Alzheimer’s until the very last stages of the disease. Music, by stimulating these preserved parts of the memory network, seems to reach into those areas of the neocortex, the brain’s wrinkled outer layer, to find those neurons that have not yet died off, thus triggering memories thought to be lost forever.

Part IV “Rocket Man”

Many caregivers and clinicians report that the memory-enhancing, mood-improving benefits of music are temporary, lasting only as long as the music is playing — and for a period of about 15 minutes afterward.

But experiments Tomaino conducted in the 1990s suggested something different. In a 1993 study, funded by a $250,000 grant from the New York State Department of Health, she was able to hire enough music therapists to administer a lavish amount of music therapy on small, five- to six-person patient groups, in 30-minute sessions, three times a week for 10 months. A battery of cognitive tests conducted before and after the therapy revealed significant improvements in brain function and behavior. Formerly silent patients, Tomaino reported, began addressing staff by name and participating more appropriately in conversations than those who participated in verbal reminiscence groups—“implying,” she wrote, “that there is a potential for improvement in patients with dementia.” In a follow-up study in 1996, 121 dementia patients also showed “significant changes in behavior and affect.”

Tomaino did not have access to an fMRI machine, so her research lacked the hard evidence of physiological brain changes — and her findings failed to gain much traction. But new research has emerged that supports Tomaino’s observations, including fMRI studies published in 2021 from a project led by Michael Thaut, a professor of music and of neuroscience in Toronto.

Thaut had always been fascinated by the power of music. Prior to becoming a neuroscientist, he had been a professional violinist in Europe. In the early 2000s, while working as a neuroscientist at the University of Colorado, he did groundbreaking research involving people with Parkinson’s disease and those recovering from stroke, showing that when rhythmically strong music was played to such patients, they synchronized their walking gait with the music and moved more quickly and with better joint control. The therapy is called rhythmic auditory stimulation. “Stroke patients walk much more symmetrically and faster,” Thaut told me recently over Zoom. “Parkinson’s patients don’t have that shuffle and tendency to fall over.”

For years, Thaut had been hearing anecdotal reports of music’s power to help dementia patients, and he had been eager to study the phenomenon. He got the chance in 2016 when he accepted a professorship at the University of Toronto and helped create a partnership with the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science and geriatric psychiatry at St. Michael’s, one of the city’s largest hospitals. His first experiments in music and memory using fMRI, in 2018, compared the effects of “autobiographically salient” music that Alzheimer’s patients had loved and listened to for 25 years or more with brand-new music created by Thaut and his team.

Patients first heard the new music an hour before they entered the scanner. When they heard it again during their scans, it had no deep encoding in the brain — it activated the auditory area only. “Basically, a sensory memory,” Thaut calls it. The beloved, familiar music, however, when played to patients in the scanner, lit up a larger network of the brain — including in the frontal lobes, where higher-order reasoning and memory are processed, a clear and objective sign of a musical “memory trigger” for people with dementia.

“They recognized it in terms of ‘that is music I know,’ ” Thaut says. “ ‘I know what that is! That is the music I danced to when I met my wife.’ This activation spreads throughout the entire cortex — and the whole network comes alive.”

He stresses that hearing autobiographically salient music does not regress patients to an earlier time of life. Quite the reverse. “It actually triggers a cognitive boost to orient them in the immediate reality. One could say, ‘Oh, they remember music from when they were 15 years old, and they feel like a 15-year-old again.’ No. They’re not suddenly acting like a 15-year-old. The music gives them a sense of orientation in the here and now—and an identity: ‘That is part of my life. I know who I am.’ ”

In a different experiment, Thaut also reported a boost in cognitive functioning — a finding similar to what Tomaino had seen in the 1990s. Alzheimer’s patients who listened to personal playlists of favorite music daily and talked about what they could remember with their spouse or caregiver for one hour a day for four weeks showed significant improvement on memory tests, Thaut says.

“That is extremely unusual. Ordinarily, these patients don’t improve in anything; if you’re lucky, you can slow down the decline ramp.” He hastens to add that he and his colleagues have not found a “cure” for Alzheimer’s or dementia. “We cannot say that we are reversing the disease, because it has a certain biological process. We are not, for instance, destroying, with music, the amyloid plaques or the tau tangles that are believed to be the cause of the memory loss. But in areas of the brain, activating preserved networks gives people at least a cognitive boost that allows them to operate in a more functional way.”

The most eye-popping of Thaut’s findings is that after four weeks of listening to their favorite music daily, patients’ brains had a greater density of white matter. “If you have an increase in white matter density or volume in a certain area of the brain,” Thaut says, “that means there are more highways active between the neurons. There’s more traffic.” A dead neuron cannot be brought back to life, but music appears to bolster connections between preserved neurons. “So we are building as much as we can around destroyed stuff,” Thaut says.

“It’s a bit like a city that gets bombed. Many houses are gone, but we can emphasize what is still standing. We can figure out how to get a street from here to there. We can rebuild to make that city support as much life as possible.”

All of this raises the question, for those of us not afflicted by dementia, of whether we should be loading up our Spotify Rocking ’70s playlists with the songs we first fell in love with in our teens and early 20s — that period of life when, according to Daniel Levitin, a musician, neuroscientist and author of This Is Your Brain on Music (2006), most people form their musical tastes.

Says Thaut, “We can assume that active and positive stimulation is good for brain health. Engaging in music you like and enjoy is definitely a great part of it. Can it reduce risk for dementia in the medical sense, like aspirin against stroke? No. There are many factors—genetics, injuries, etc.—that contribute to disease. But it may provide boosts to keep the brain healthy longer.”

And don’t worry about friends or spouses who deride you for engaging in empty nostalgia when you fire up Elton John’s 1972 banger “Rocket Man” for the 20th time that month. It is precisely the familiarity of such music, the memories around it, the goose-bump-inducing pleasure of its soaring chorus and the surge of dopamine that can be released by your brain’s pleasure and reward centers as that crescendo arrives— “I’m a rocket MANNNNN … And I think it’s gonna be a long, long time!” — that can make such beloved songs so therapeutic, according to Thaut. “This is your daily brain exercise,” he says. “As a general principle: If there’s something that’s good for you, do it as much as you can.”

Listening to new music has its own rewards, of course — what better way to bond with a tween than over Taylor Swift? But for revving up the memory centers embedded throughout your brain, science seems to suggest that familiar tunes work best.

Part V “She Loves You”

I learned firsthand about the miraculous power of music for dementia patients in November 2020, when, for this magazine, I was researching a story about Tony Bennett’s previously undisclosed Alzheimer’s disease.

Visiting him in his apartment on Manhattan’s Central Park South, I saw a man unable to converse, who barely registered my presence and who, I was told by his wife, Susan, had forgotten the use for common objects like a fork or keys. Yet when his longtime piano accompanist began to play, Bennett, at the sound of the first notes, came alive, walked to the piano and proceeded to perform, impeccably, an hour of music from his set, recalling every lyric, crescendo, melody, physical gesture. It was impossible to believe he was in the late stages of a devastating illness that two years later would end his life.

Now, once again writing about music and memory for AARP The Magazine, I am delighted to discover that, like Bennett’s, my own memory is unlocked by musical triggers. I have, for the last couple of years, been writing a memoir and, at age 65, I find that I am getting to it just in time before certain salient aspects of my past have faded from my synapses forever.

Recently, I was revising a chapter concerning my earliest memory of my late mother — a memory from when I was 4 years old, in my native Toronto, and we were drawing on sheets of brown packing paper while the radio played a song that had just burst onto the Canadian airwaves and caused a sensation. It was called “She Loves You,” and it was by a new group named the Beatles.

The date was September 1963, which I can state with accuracy because that is when the song debuted across North America. Though a massive hit in Canada, the song flopped in the United States — the Beatles would have to wait more than four months for a U.S. hit with the release of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and their epochal appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show.

In any case, in my original draft of this scene, the details were annoyingly hazy. I knew my mom was encouraging my nascent skills as a cartoonist, but all was dim and undefined, lacking the specific detail that makes writing come alive. But thanks to my experience with Tony Bennett, and my more recent encounters with Connie Tomaino, Xiyu Zhang and Michael Thaut, I decided to listen to “She Loves You” as a memory prod.

Reader, I might as well have discovered that someone had secretly filmed and recorded my mother and me that distant afternoon. Now, with the music as spur and prod to my memory, I could “see” that, on that day six decades ago, I was drawing the Beatles’ faces on that packing paper — and that my mother, to aid me, had laid out, open on the floor, a sheet of newspaper that featured photos of the Fab Four.

Pointing to each face in turn and saying their names (“Paul … John … George … Ringo”), my mother was brought back to life, de-aged to a youthful 31, and I could see her nimbus of soft brown curls, her large green eyes, her huge smile — That’s my mom! — as she exclaimed over my attempt (failed, as my revived memory assures me) to capture the Beatles’ individual looks. It was a heart-stopping journey back in time, a resurrection that, frankly, moved me to both smiles and tears.

At least for as long as the music played.

Journalist John Colapinto is a longtime contributor to The New Yorker and Rolling Stone and author of As Nature Made Him and This Is the Voice. He profiled Jimmy Buffett in the December 2021/January 2022 issue.